It was the ultimate college acceptance — albeit with a bit of a twist.

The message came by phone and the recipient, Joe Bertolino, had been invited to become Southern’s new president. Roughly eight months later, Bertolino is no longer the new kid in town. Since officially taking the helm at the university on August 22, he’s quickly become “Top Owl” in name and deed, crisscrossing campus, New Haven, and beyond in an ongoing quest to connect with students, alumni, and business and community members.

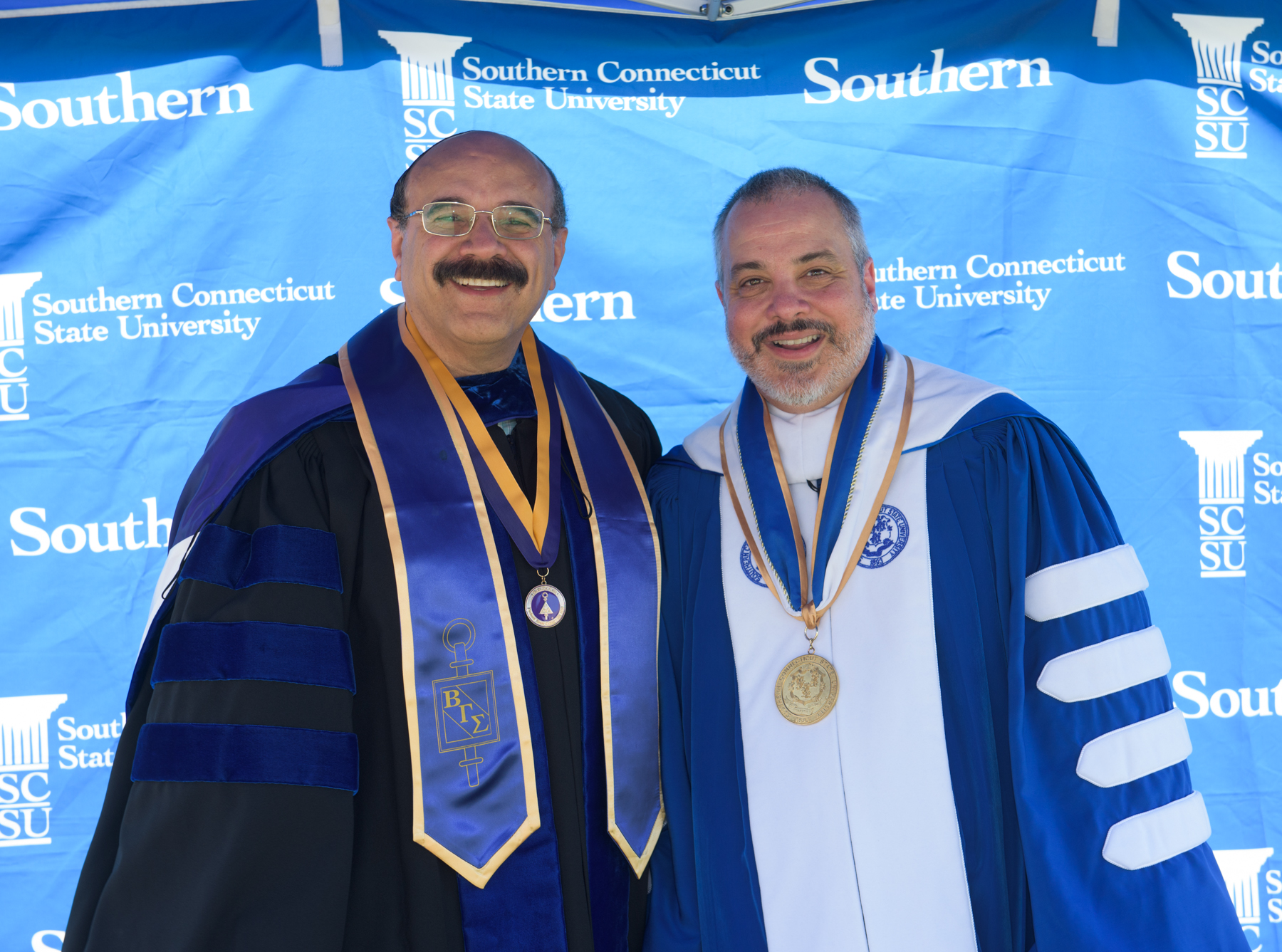

In recent months, Bertolino — or President Joe as students call him — has met with scores of legislators and industry leaders, joined the board of directors at the Central Connecticut Coast YMCA and New Haven Promise, rolled up his sleeves at the university’s day of service, jointly led an on-campus social justice forum with his partner and fellow higher education leader Bil Leipold, and connected with neighborhood schools. Among the Owls most vocal fans, he’s even tackled the t-shirt cannon, gamely shooting Southern swag to the cheering crowd at Jess Dow Field.

“Since his first days on campus, he’s been incredibly involved,” says Corey Evans, a senior political science major and president of Southern’s Service Commission, which runs student-led community outreach programs. “He’s very committed to social justice. It’s one thing to talk about it, but he puts himself out there, helping with planning and going to events. . . . When I look back at Social Justice Week and the other programs that were held on campus during his first semester, I can’t wait to see what’s next.”

Such commitment is a given says Bertolino, who has 25-plus years of leadership experience at private and public universities, the latter in Vermont, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania.

“I come from a social work background. I firmly believe it’s all about relationships — and students always come first.”

Before Southern, he was president of Lyndon State College in Vermont for four years, spearheading the development of new master and strategic plans, the launch of nine academic programs, and an almost 200 percent increase in annual giving in three years.

He joins Southern at a pivotal time, highlighted by the dramatic transformation of campus, including the construction of a state-of- the-art science building, a new home for the School of Business, and the expanded Hilton C. Buley Library, now twice its original size. The obstacles facing the university are dramatic as well, including a statewide budget deficit and a shrinking population of high school graduates. But Bertolino remains upbeat.

“In terms of our financial position, yes, we are facing challenges,” he says. “But I don’t want to lose sight of the fact that we have a lot to be proud of. When I look out over this campus, I see great facilities. Great research opportunities. Great faculty. A strategic plan that I am very excited about and will be particularly aggressive about implementing.”

A longtime social justice educator, Bertolino has pledged to continue championing the cause. In November, he became one of an initial 110 college and university presidents to issue a joint letter to then President-elect Donald Trump urging a forceful stance against “harassment, hate, and acts of violence.”

It’s a message he’ll be sharing throughout Southern and the community-at-large. “At the moment, I am going to be out and about a lot. It’s kind of nonstop,” says Bertolino. Following, he pauses briefly to share some personal stories and his thoughts on the university’s future.

What role did education play in your family?

I’m the product of a traditional lower-middle class family, born and raised in the suburbs of South Jersey. Faith, family, and education were the priorities in our home — in that order. I had 16 years of private school education. My younger sister and I attended a catholic grammar school and high school. I went on to the university of Scranton, a catholic college in the Jesuit tradition. It was always assumed that my sister and I would go to college. It was just something you never questioned.

How about your parents?

Neither of my parents initially had a college degree when i was growing up. My father had a high school education and took some community college classes. He worked for the shipyard in Philadelphia and, later, for what was then bell Telephone. He was a switch operator before going into management. My mother went to nursing school after she graduated from high school. At the time, people typically didn’t think about getting a college degree to become a nurse. But when I was in about seventh grade, my mother went back to school to get a BSN [bachelor of science in nursing].

Did that make an impression on you?

Absolutely. She worked very hard. I consider myself to be a first-generation college student in the traditional sense. But my mother was the first in the family to get a college education, which she did as an adult while simultaneously raising a family.

What was your college experience like?

When I look back at grammar school and high school, it’s all a blur. I don’t have negative memories, but they’re not particularly fond either. But college was amazing. That’s one of the great benefits of higher education. It gives you the opportunity to reinvent yourself a bit . . . to explore. You find your cohorts . . . your people. I was in a group that included the band and singers. Last year, I went back to my alma mater to celebrate our former director’s 35th anniversary. Here it was 30 years later, and I was so excited to see everyone.

Your parents have many fans on campus. They made great comments about being proud of you on Facebook.

It’s very, very sweet. [laughs] My mother always emphasized education, but it was important to my father, too. He started his professional life as a blue-collar worker and worked very hard. The summer after I graduated from high school, he found a job for me at a cable TV factory. Later, when I was packing to leave for college, he came to my room and asked how I had liked working there.

‘I hated that job,’ I told him. ‘It was horrible. horrible.’ He looked me in the eye and said, ‘And that is why we are sending you to college. Don’t forget it.’ I never did.

Now, both my sister and I work in education. She works in pre-K and here I am in higher education.

You recently were named to the board of directors at the Central Connecticut Coast YMCA. You’ve had a long association with the YMCA. How did it start?

It was the summer after my freshman year of college. The local newspaper — the Courier-Post — had a job listing: ‘Counselors Wanted.’ I remember thinking, ‘I’m majoring in psychology. I can be a counselor.’ I didn’t have a clue. . . . So I went to the interview. Drove up and there’s a big sign: YMCA Camp Ockanickon [in Medford, N.J.] I went to the director’s office, and he proceeded to ask me a series of questions. Have you ever been to camp? Nope. Do you swim? Nope. Play any sports? No. Boat? Nope. Practice archery? No. Arts and crafts? Maybe. Umm, no.

How about working with children? I’d like to, I told him — and he thanked me and I left. Soon after my mother called to tell me they’d offered me the job . . . which I thought was just crazy.

So was that director right? Was it a good fit?

I worked at camp every summer — both when I was in college and, after, while working as a high school teacher. I went on to serve on the camp’s board of directors for 13 years and was the president of the board from 2006 to 2010.

It’s the relationships that stand out. I met Stephan, one of my first campers, when he was 9. His parents were getting divorced that first year. From then on, he came back and stayed in my cabin every summer. Eighteen years later, I was the best man at his wedding. His oldest son, Matthew, is my godson. Last summer we sent Matthew off to Camp Ockanickon, where he stayed in the cabin where his dad and I met.

Camp has been the single most important influence in my life. I credit the fact that I am sitting in this chair — that I’m the president of Southern — to that camp.

An article in Vermont Business magazine mentioned that you contemplated becoming a priest?

I was in the seminary in Scranton for a year and a half. In hindsight, it was far more conservative than I would have liked. But I didn’t leave for religious reasons or a lack of faith; I left because I wanted to forge my own path — and that presented an unexpected opportunity. I took a leave of absence and was assigned to teach religion at a Catholic school in South Jersey. I never went back to the seminary. Teaching led to graduate school, which led to my starting a career in Student Affairs in higher education — and I’ve never left higher education.

What led you to pursue the presidency at Southern?

Southern is a highly diverse community located in a great, culturally rich, urban environment. The university educates many first-generation college students and is positioned to be a strong community partner — the traits that I really love in a university setting. New Haven is also a great city, and it’s a lot closer to my family than Vermont. My partner Bil and I talked about it — and I thought I had nothing to lose by throwing my hat into the ring. It’s a great opportunity. So here I am. Bil and I recently closed on a home in Morris Cove in New Haven. We are excited.

You’ve been described in the press as one of the country’s first openly gay university presidents. Does that carry an added responsibility?

When I started at Lyndon [State College] there were about 20 to 25 openly gay presidents in the U.S. There are now about 70 to 75. I do think that for the LGBTQ community — and also for the Student Affairs community — I feel an added responsibility to “represent” . . . to go above and beyond. But I also remind folks that I am not the gay president. I am the president who, by the way, just happens to be in a committed relationship with a man. Period. It’s not really a focus for me and the work that I do. That said, I am certainly honored if my role at Southern inspires others — lets them see the possibility of holding a public leadership position.

Describe your leadership style in five words.

Compassionate. Kind. Collaborative. Relationship focused.

What are your immediate goals for Southern?

Topping the list, I would like Southern as a community to become even more focused on social justice — in every possible way. I have been a social justice educator for more than 25 years, and my administration will be committed to social justice, not just in word, but in action and deed. Secondly, raising the profile of the institution is key. As I said during my interview [for Southern’s presidency], ‘I’m a PR man!’ I welcome the opportunity to share Southern’s accomplishments and all the benefits it offers to our students, our community, and the state. Third, we will be having solid discussions to address our financial challenges through the promotion of entrepreneurship, the development of new and innovative community partnerships, and a greater emphasis on private fundraising. And this is extremely important to me — we are focusing on student success, furthering efforts to enhance academic excellence, remove obstacles to graduation, and improve retention.

Last summer, prior to officially becoming president, you attended an on-campus dialogue, “A Campus Conversation on Race, Policing, Advocacy, and Action.” You briefly shared your concerns for Joel (pronounced Jo-el), a young man from Jamaica.

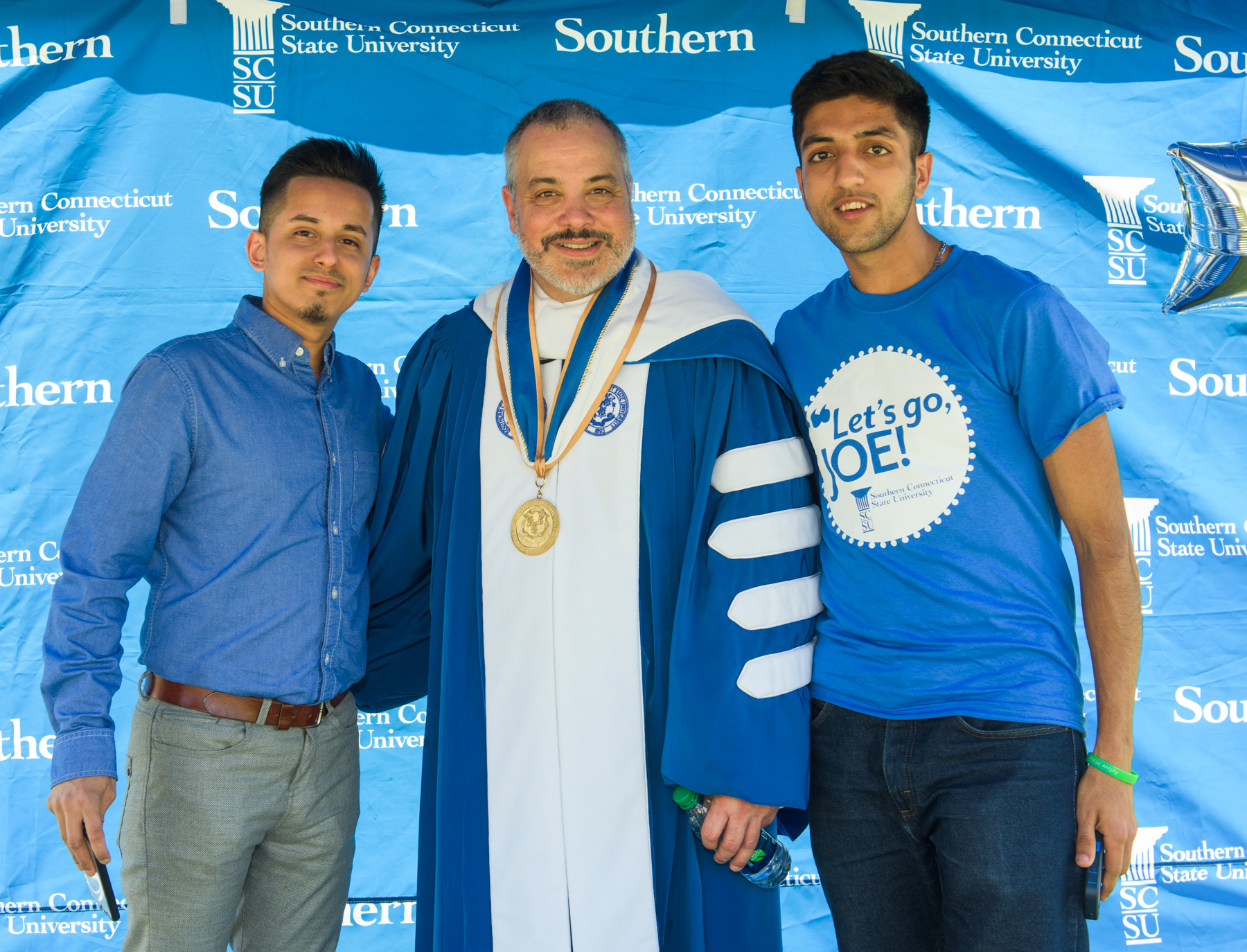

My family is very nontraditional. I refer to Joel as my son, though he’s not in a legal sense. But I believe family is defined by love, not by blood or paperwork. When Joel’s first baby was arriving, he told me, ‘You are going to be a grandfather.’ His son Roman calls me Grandpa Joe.

It’s important for people to know how we define family . . . who in our lives are important to us — especially if this helps me to better understand the young men and women at Southern.

[Bertolino first met Joel Welsh Jr. at Queens college. Then a student, Joel worked as his exercise trainer. Today, he is the head strength and conditioning coach at Delaware State University.]

You’ve invited the students to call you President Joe. Why is this important?

I want members of the community to think of me as a person . . . a member of the community. I also want to be somewhat informal. But that doesn’t take away from the seriousness of my role. I tell people not to confuse my smile and my informality with a lack of seriousness. But too many times, people get stuck in their own hype. I think ‘President Joe’ invites people to engage in a conversation and build a relationship.

Speaking of conversations, you’ve been talking to many constituencies — from students and alumni to faculty to legislators. Have you learned anything that surprised you?

One thing I am really excited about is the quality and the caliber of our student population. The academic excellence and rigor at Southern is far beyond what many realize. Our students are sometimes underestimated. In the sciences, a team of Southern students recently won a bronze medal at an international synthetic biology competition. Southern’s Society of Professional Journalists was named the Outstanding Campus Chapter in our region [Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island]. Our freshman class includes many top students, including three high school valedictorians. We are a community of scholars, artists, and community activists. I’m looking forward to seeing all that we accomplish.

— This article was featured in Southern Alumni Magazine, Spring 2017