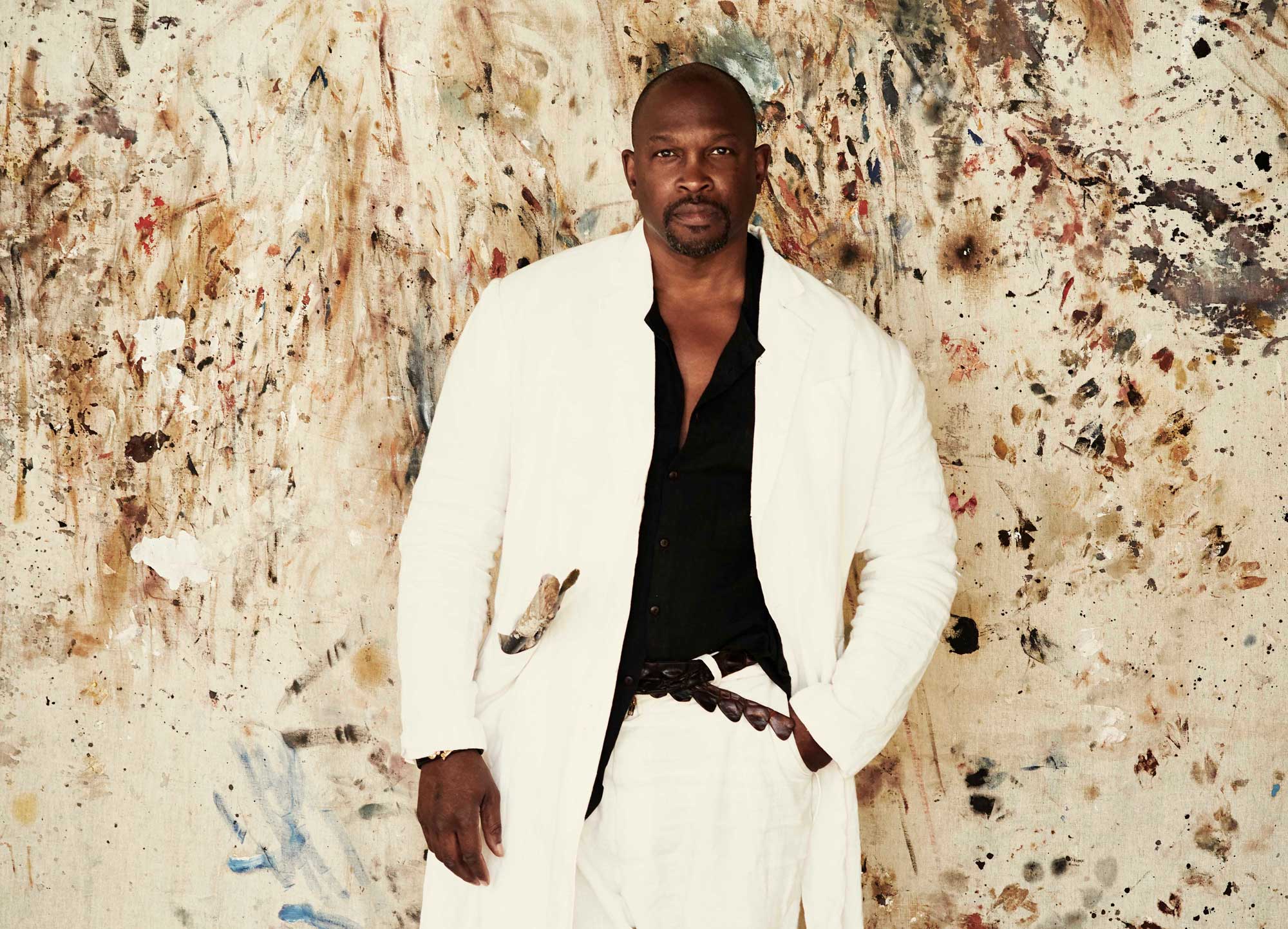

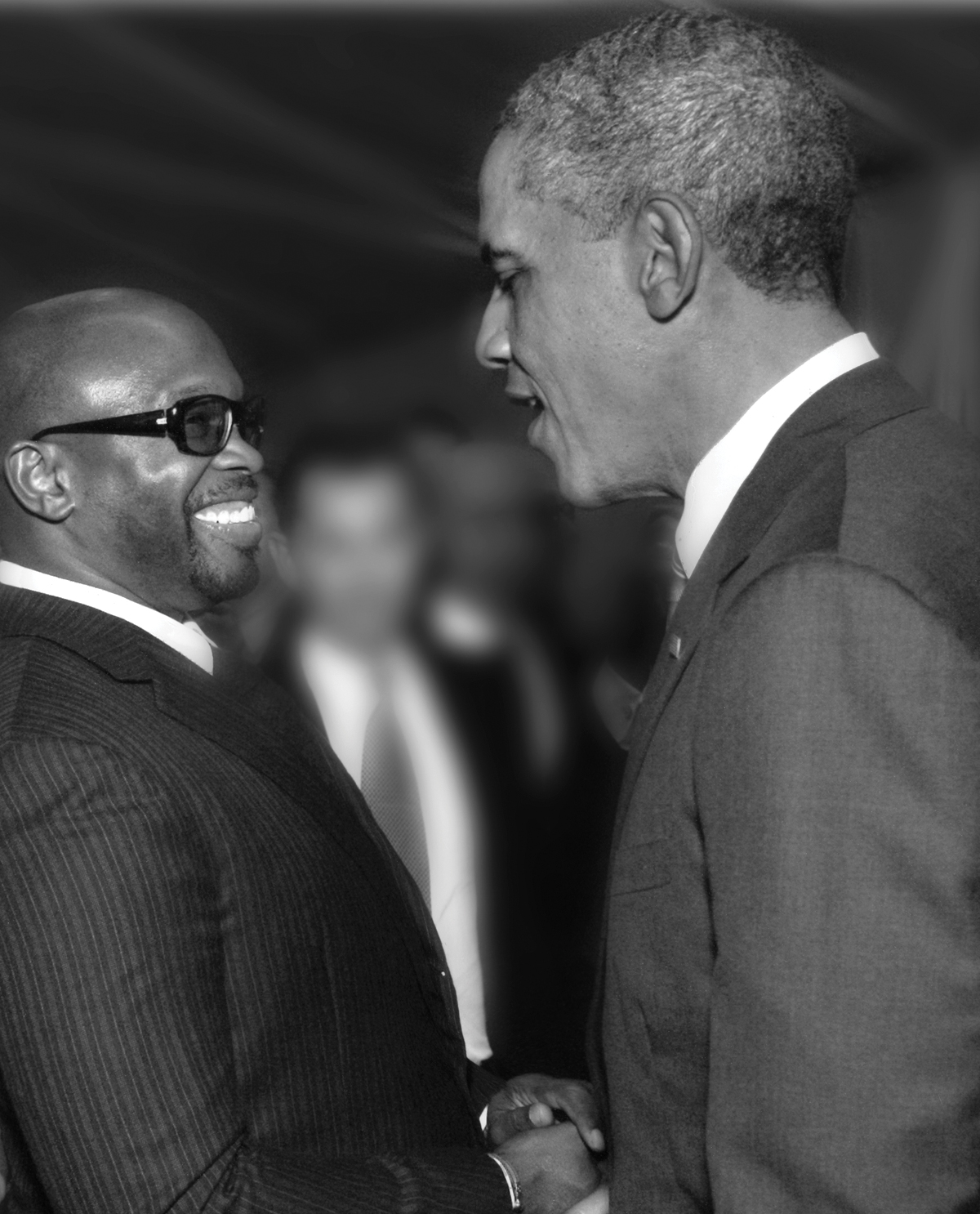

Chaz Guest, ’85, may not be a household name, but his work has been embraced by many big ones. Herbie Hancock and Vanessa Williams collect his paintings. Former President Barack Obama hung his portrait of Thurgood Marshall in the Oval Office. Oprah Winfrey praised a portrait of Maya Angelou as a little girl that she had commissioned from Guest: “Saying the painting is beautiful is too mild of a word.”

with former President Barack Obama, who hung Guest’s portrait of the late Thurgood Marshall, the first African-American Supreme Court Justice, in the Oval Office.

Guest arrived at Southern as a gymnast on scholarship, not knowing what direction he wanted his life to take. He left after studying graphic design with an inkling he had become an artist. He credits David Levine, his art history professor, and the late Howard Fussiner [professor emeritus of art], the only painting teacher he ever had. “Those two put me on the path of the life I have now as a painter,” Guest says from his studio in Los Angeles, brush in hand, working on a portrait of the abolitionist John Brown while we speak. One of Fussiner’s landscapes hangs on the wall.

Levine introduced Guest to the history of art. Fussiner encouraged him to become part of it. The painter — who reminded Guest of Salvador Dali with his wild white hair, quirkiness, and energy — encouraged Guest by praising his work in front of the class. He also passed along commissions to paint watercolors of people’s homes. “He opened my eyes to the idea that I could paint something and actually earn some money,” Guest says.

After studying at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York and a brief stint illustrating fashion magazines in Paris, Guest devoted himself to his own painting. He sold his first work on the sidewalk outside his apartment in New York City. With that money, he bought a larger easel and more supplies and was on his way. Today, the artist is represented by the Los Angeles-based Patrick Painter Gallery. His work has been shown in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Tokyo, and Paris.

A devotee of Kyokushin karate, which his older brother taught him upon returning from the service in Okinawa, Japan, Guest has used the martial arts to open his mind and dedicate himself to his art. An aging hip prevents the 58-year-old from regularly practicing karate, but he still applies the mental principles. “Martial arts is a way of life,” he says. “I certainly have it in mind.”

His influences range from Fussiner to Balthus, from Dali to Picasso. Inspiration also comes from musicians — Pavarotti to Mahalia Jackson, but especially his beloved jazz. Thelonious Monk. John Coltrane. He has painted them and frequently plays their music in his studio while working. He’s also created paintings on stage inspired by live jazz performances. He starts without preconceived notions of what he is going to paint and improvises along with the musicians. “It’s best to have a blank mind, and flow to the vibrations and spirit of the music,” he says.

Guest works in a variety of mediums. His Geisha Series, created on Japanese zori sandals, was inspired by a trip to Japan, and his Cotton Series, portraits of enslaved men, women, and children, is done on cotton picked from Southern fields, where the subjects might have toiled.

After admiring Guest’s Cotton Series, Yahya Jammeh, then president of the Republic of Gambia, invited him to visit in 2010. Guest painted an oil portrait of Jammeh as a gift, which he presented upon his arrival. “It was a life-changing trip,” Guest says.

A stop at James Island in the Gambia River to see the remains of a fort used by British slave traders was particularly profound. Guest spent time alone in a holding cell. “I felt all of my nightmares as an African-American started in this one place,” he says. He wept. Anger and sadness washed through him. He emerged transformed. “Afterward, I felt new,” he says.

Guest suggested that the island be renamed Kunta Kinteh Island to honor the slaves who passed through. Jammeh agreed and the name was officially changed in 2011. For the occasion, Guest sculpted a Mandinka warrior rising out of one of the island’s many baobab trees and escaping the shackles of slavery. He called it Freedom. It was not installed as a 30-foot statue on the island as originally intended, as it lacked the support of the president who succeeded Jammeh.

But the bronze sculpture was chosen for the statuette of the ICON MANN Legacy Award, most recently presented to Spike Lee, Samuel L. Jackson, and Ruth E. Carter, winner of the 2019 Academy Award for costume design on the film, Black Panther. The Legacy Award honors those whose body of work has positively transformed the narrative and trajectory of black culture.

For all of his success as an artist, Guest is proudest of his role as a father. He has two sons, Xian, 16, and Zuhri, 25. He wears a bracelet made from a mold of their umbilical cords. “I enjoy being a father of two great boys,” he says.

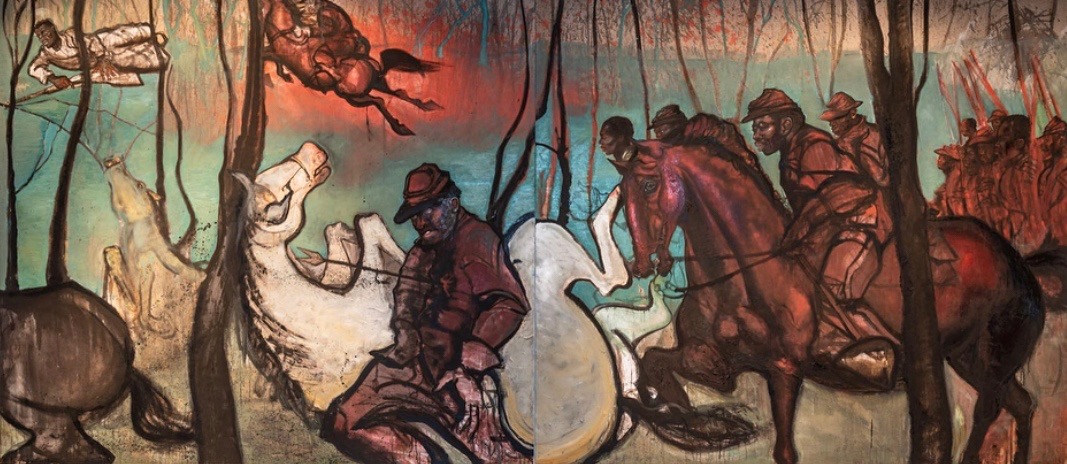

Guest’s latest project is Buffalo Warrior, a graphic novel he wrote about a boy born into slavery in the 1800s who becomes a modern-day superhero. Guest illustrated the book in Japanese sumi ink on handmade paper — and also painted a series of the hero in oil and another related series entitled Buffalo Soldiers. He’s in discussions with movie studios to turn the story into a feature film.

He sums up his aesthetic, which is particularly apparent in the Cotton Series and Buffalo Warrior: “I wanted to start from the root of our American experience, which happens to be slavery. So I wanted to go back there in that time and paint with everything I have to convey dignity and love and [that] they’re people, not only slaves. If you want to make a good painting, you’ve got to paint what you love — and I love those people.”