During the late 19th century, Armenian photography studios were prominent throughout the Ottoman Empire, now known as Turkey. Much photographic output was lost in the 1915 Armenian genocide, and because of this loss, the traces that remain have taken on greater importance due to the physical erasure of Armenian cultural heritage from the region.

Armen T. Marsoobian, professor of Philosophy, was recently awarded the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Mellon Foundation Fellowship in Digital Publications for his work using surviving photographs to provide a window into this lost Armenian world. His project, “A Virtual Exhibition of Ottoman Era Anatolian Armenian Vernacular Photography, 1880s -1920s,” is now well under way; Marsoobian has assembled a team including a digital graphic designer, a curator, and tech help for web design. The stipend was $60,000 and is being used to support the expenses of the project.

NEH-Mellon Fellowships for Digital Publication are awarded to scholars engaged in humanities research that requires digital formats and digital publication. Only 8 percent of applicants were awarded the prestigious scholarship, and Marsoobian is the only recipient from Connecticut.

“These surviving photographs tell the story of the peoples and the cultures lost during the early decades of the 20th century,” Marsoobian writes. “Photographs provide a window into this lost Armenian world. Recreating this world and understanding the important role that vernacular photography played for Armenians before, during, and after the 1915 events is a central goal of this interactive virtual exhibition and the accompanying multimedia e-book catalog. Visitors to the exhibition will explore the content, context, and afterlife of the photographic image.”

For Marsoobian, this project is of personal significance. Marsoobian’s grandfather and great-uncle, Tsolag and Aram Dildilian, were photographers employed both by Anatolia College in Marsovan, a town in Ottoman Turkey, and the local government. From 1890 to 1922, Tsolag was a significant photographer in the region where the family resided.

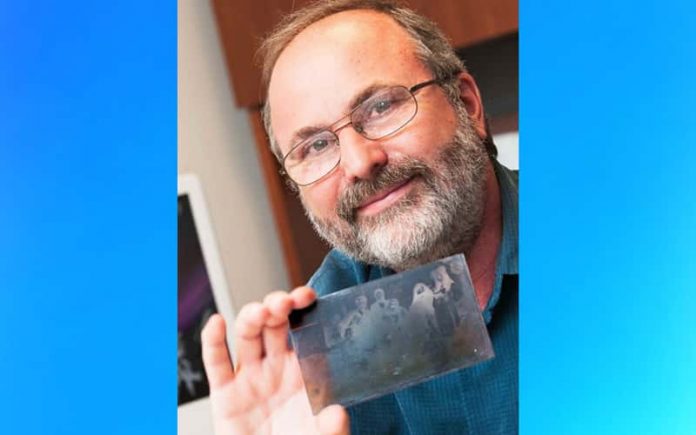

A large collection of photographs and glass negatives came down to Marsoobian from his “family of many photographers,” and he now possesses over 600 photographs from the Dildilian brothers’ collection, many of which date from the period 1910 to 1922, which encompasses the years of the Armenian Genocide.

The Armenian Genocide, says Marsoobian, refers to the deliberate and systematic destruction of the Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire during and just after World War I. It was implemented, he says, through wholesale massacres and deportations, with the deportations consisting of forced marches under conditions designed to lead to the death of the deportees. The total number of resulting Armenian deaths is generally believed to have been between one and one and a half million.

Anatolia College is now located in Greece, and in 2009 Marsoobian was invited to the college to give several talks based on the photography collection. In doing research about the collection and his family history, Marsoobian received new information from members of the family. He learned that quite a bit had been written by his great-uncle and his great-aunt’s daughter pertaining to the photographs, including include two lengthy memoirs, as well as family letters and diary entries.

Marsoobian explains that Armenians were a minority in Ottoman, Turkey, but were instrumental in having Anatolia College come to Turkey. At first, the students primarily came from the Armenian and Greek communities. Marsoobian says that although there were Turks who tried to help Armenians, the Turks generally avoid the use of the word “genocide” and instead refer to the “catastrophe of 1915” or “events of 1915.” For the first time a few years ago, there were public commemorations of the genocide in Turkey.

Marsoobian previously wrote a prize-winning essay dealing with the efforts of his grandfather and great-uncle in rescuing 30 young men and women in the period 1915 to 1918 in their hometown of Marsovan. He has also given lectures on the photography collection and created an exhibit – “Bearing Witness to the Lost History of an Armenian Family through the Lens of the Dildilian Brothers” — that was on display in 2013 in a gallery in Istanbul, Turkey, among other venues. He has also published two books on his family’s remarkable photography collection and its significance to the Armenian Genocide.

****************

Our Philosophy Department offers a world-renowned faculty and a wide variety of classes, many of which satisfy university requirements. Learn more.