The first time John Priest went to Southern, he dropped out to chase a baseball trainer’s job in New Hampshire.

“Being young and foolish, I did OK in school, but not great,” said the 38-year-old Cheshire native, who was majoring in exercise science at the time. “Then in 2002, I just kind of stopped going.”

In the years that followed, Priest got married, became a dad, and eventually earned an associate degree in respiratory therapy, trading the baseball gig for a hospital job.

Later this month – 20 years after he first enrolled − he will don a cap and gown and finally earn his bachelor’s degree as the first graduate of Southern’s Associate of Science to Bachelor of Science in Respiratory Therapy (A.S. to B.S.R.T.) program.

“It’s a long time coming,” said Priest, who now lives in Stow, Mass. with his wife and two children, a daughter, 8, and son, 5.“It’s even more of an honor to be the first one.”

Southern launched the program in the fall of 2015 in response to a national push for respiratory therapists to earn bachelor’s degrees, said Joan Kreiger, respiratory care program coordinator at Southern. Eligible students must be certified respiratory therapists and hold an associate degree in respiratory care.

Leaders at three Connecticut community colleges – Manchester, Norwalk and Naugatuck Valley — approached the university about starting a program for students who wished to continue their studies, Kreiger said.

Those community colleges offered two-year programs in respiratory therapy, but at the time there were no public bachelor’s degree programs anywhere in New England, Kreiger explained.

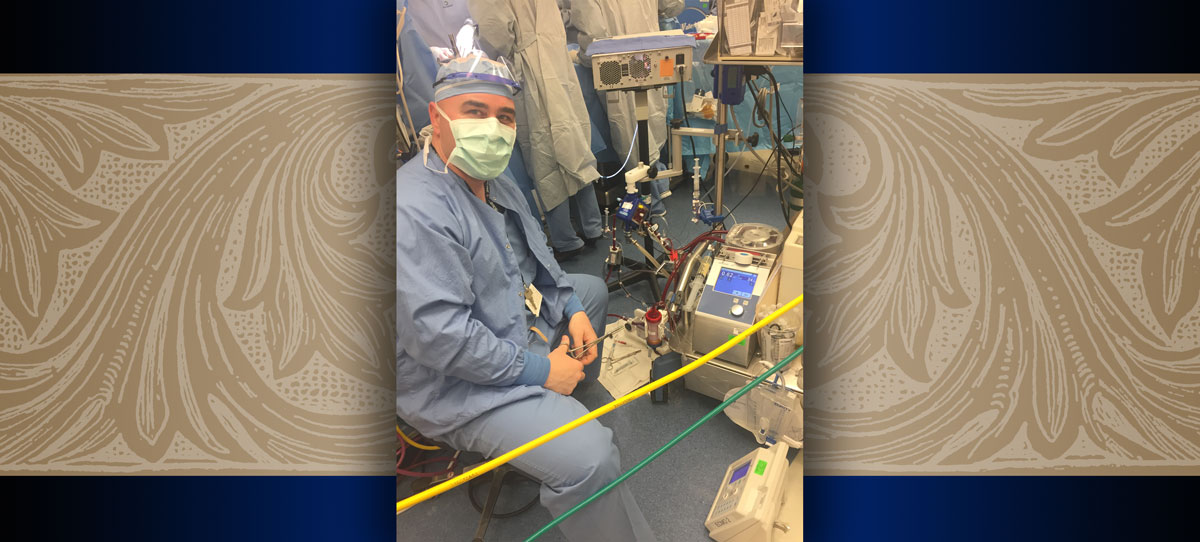

Priest, who completed the bachelor’s program online, said he hoped a bachelor’s degree would propel him into a research or management role at Boston Children’s Hospital, where he works full time as an ECMO specialist. (ECMO is a form of respiratory therapy that uses a heart and lung machine to oxygenate the blood. (It technically stands for Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation.)

So far, he’s off to a good start. Priest’s capstone project at Southern has piqued the interest of the surgical staff at Boston Children’s and could lead to changes in hospital protocol if his findings stand up to further study, he said.

“It was quite an impressive presentation,” said Kreiger, who traveled to Boston Children’s for the presentation along with Sandra Bulmer, dean of the School of Health and Human Services. “It was extremely professional and he’s obviously well-regarded by his colleagues.”

Priest’s project evaluated the way blood clotting is monitored in infants undergoing ECMO therapy. Since blood clots are a major risk factor in ECMO, patients, including newborns, are given the blood-thinner Heparin during therapy, he explained. But too much can lead to a brain bleed, another potentially deadly complication.

At Boston Children’s, newborns on Heparin are checked hourly using the Activated Clotting Time (ACT) blood test, which measures the time it takes for the blood to form clots. If the numbers are out of range, the Heparin dose is adjusted.

Priest said the ACT is already known for having a high margin of error, but his research found the test and others like it are even less reliable in newborns, whose clotting factors haven’t fully developed. As a result, changing the dose based on hourly readings could lead to over- or under-medicating the baby.

“My idea was instead of treating the actual number (every hour), we start treating the trend,” he said. “If we do see an upward trend after three hours, that’s when we’d start decreasing the dose.”

Priest’s next step is to expand the study to more patients and if the data holds up, he will present it to a committee of surgical and ICU attending physicians, some of whom have already indicated their openness to changing the protocol.

He is also co-authoring an article about the study for AARC Times, the monthly magazine of the American Association of Respiratory Care, a challenge he said he feels especially prepared for thanks to his courses at Southern.

“Getting better at scientific writing and being able to speak the language of (academic research) was probably the best thing to come out of it,” he said of enrolling in the program.

Kreiger said she was thrilled Southern would be graduating its first respiratory therapy student, and even more excited it is someone like Priest “who really embraced the whole experience.” She said she hopes his story will inspire other adult learners, who make up a majority of the program.

“It does take quite a leap of faith and a big support system sometimes to come back to school in the middle of life,” Kreiger said. “John just exemplified how it could be done, not only well, but expertly.”

Photos courtesy of Boston Children’s Hospital