Mentorship matters to future scientists — especially undergraduate and graduate students who are members of underrepresented groups, including women, people of color, and first-generation college students. So, concludes a 288-page report issued by the National Academies* —findings Peter J. Werth is addressing head-on in his dual roles as entrepreneur and philanthropist.

A business leader with the soul of a scientist, Werth is committed to supporting the next generation of researchers among Southern’s students and forwarding Connecticut’s science-based businesses in the process. He comes by this focus naturally. A first-generation college graduate, he is the founder, president, and chief executive officer of ChemWerth, a full-service, generic drug development and supply company with offices in Connecticut and internationally.

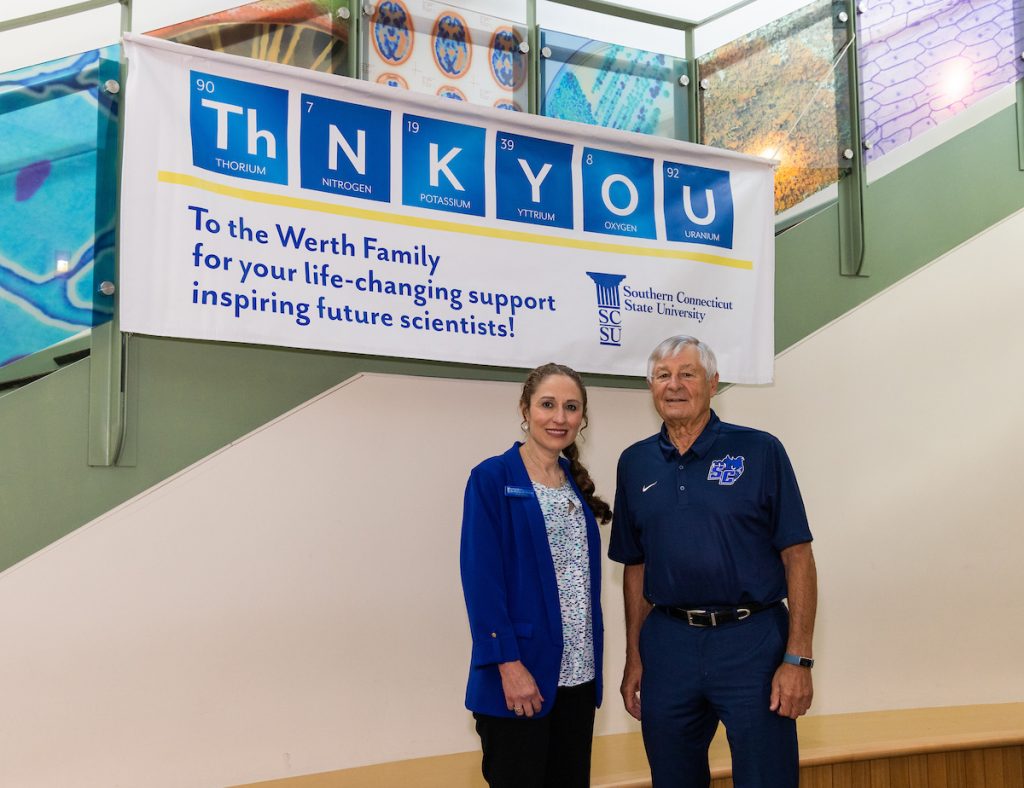

Werth is also the university’s largest benefactor, who has committed $7 million to the SCSU Foundation in the past decade. Included in this sum is a $3 million pledge made in 2022, to be paid over eight years, much of which will support the newly named Werth Nanotechnology Industry Academic Fellowship, an initiative that provides undergraduate and graduate science majors with research and business experience, and, above all, mentorship. The gift will establish an endowed fund to maintain the fellowship program in perpetuity.

“Programs that build and educate the next generation are a priority,” says Werth. “Our family has close ties to Connecticut. We appreciate Southern’s commitment to building the state’s workforce as well as its focus on research connected to the community.” The gift reflects Werth’s belief in the importance of public higher education. He received his bachelor’s degree from Fort Hays State University in Kansas, prior to earning a master’s from Stanford University. “I believe that state universities are the engine that powers Connecticut’s economy,” he says.

The Werth Center for Coastal and Marine Studies at Southern, named in recognition of Werth’s $3 million gift announced in 2013, exemplifies this regional focus. Through the center, students and faculty have collaborated on research on a host of topics, ranging from the water quality in local rivers and harbors to the temperate coral Astrangia poculata found in Long Island Sound to the effectiveness of efforts to address beach erosion.

The Werth Nanotechnology Industry Academic Fellowship Program also has a strong connection to the state and the region. It was launched at Southern in 2013 as a pilot program with Werth’s support. He had long been intrigued by the burgeoning nanotechnology field, which can be simply defined as science, engineering, and technology conducted at the nanoscale (about 1 to 100 nanometers). A sheet of paper is about 100,000 nanometers thick. A strand of human DNA is 2.5 nanometers in diameter.

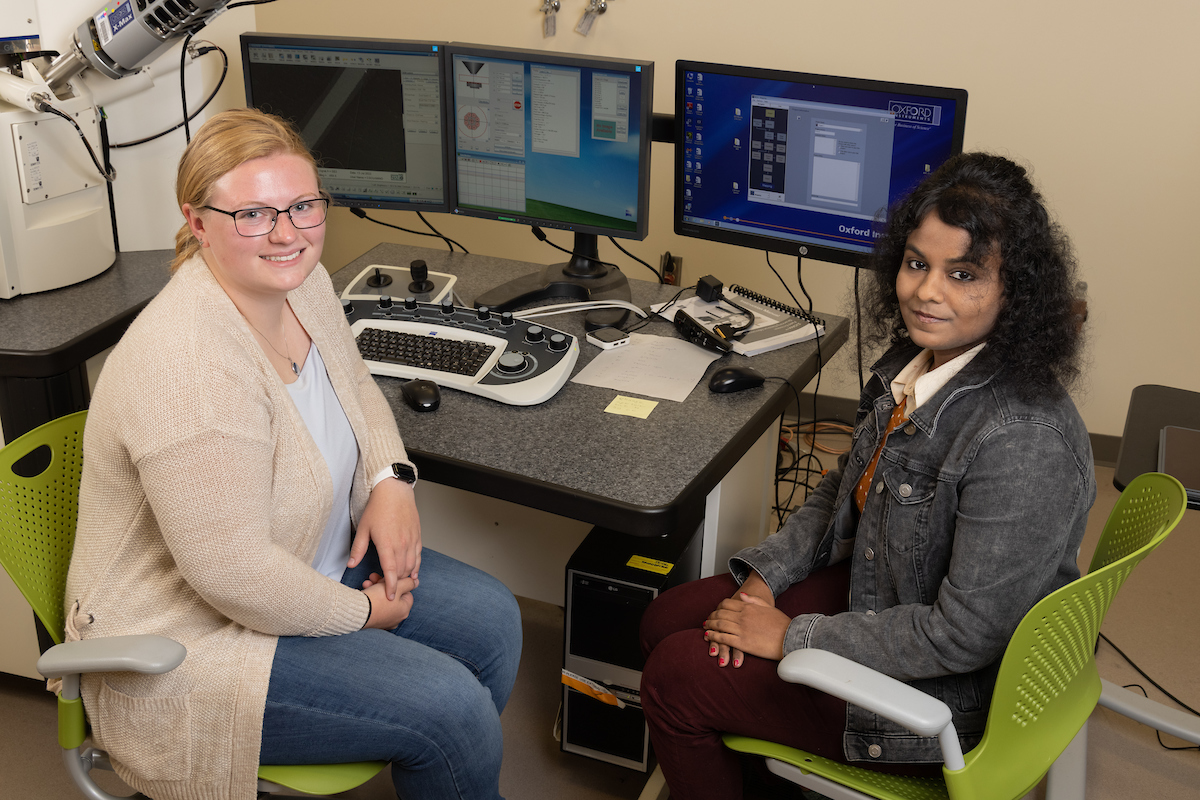

Werth envisioned a program that would allow students to conduct laboratory research in the field, grounded in a real-world business environment. The resulting program — then operating as the Industry Academic Fellowship — is based at the Connecticut State Colleges and Universities Center for Nanotechnology, located at Southern, and operates under the direction of Christine Broadbridge, professor of physics and the executive director of research and innovation at the university. Broadbridge is an award-winning industry leader — the past president of the Connecticut Academy of Science and Engineering who was recently elected to the Board of Directors of the Materials Research Society. And her regard for Werth couldn’t be higher.

“Peter Werth is an entrepreneur scientist who is an inspiration to our students and faculty mentors alike,” she says. “He had the vision from the start (close to ten years ago) to understand the importance of combining nanotechnology with business and entrepreneurship to create the unique Werth Industry Academic Fellowship. We were ahead of our time with the result being a highly successful program that has impacted so many. Close to 100 students have participated in the program, with a large percentage from underrepresented groups in STEM [science, technology, engineering, and math].”

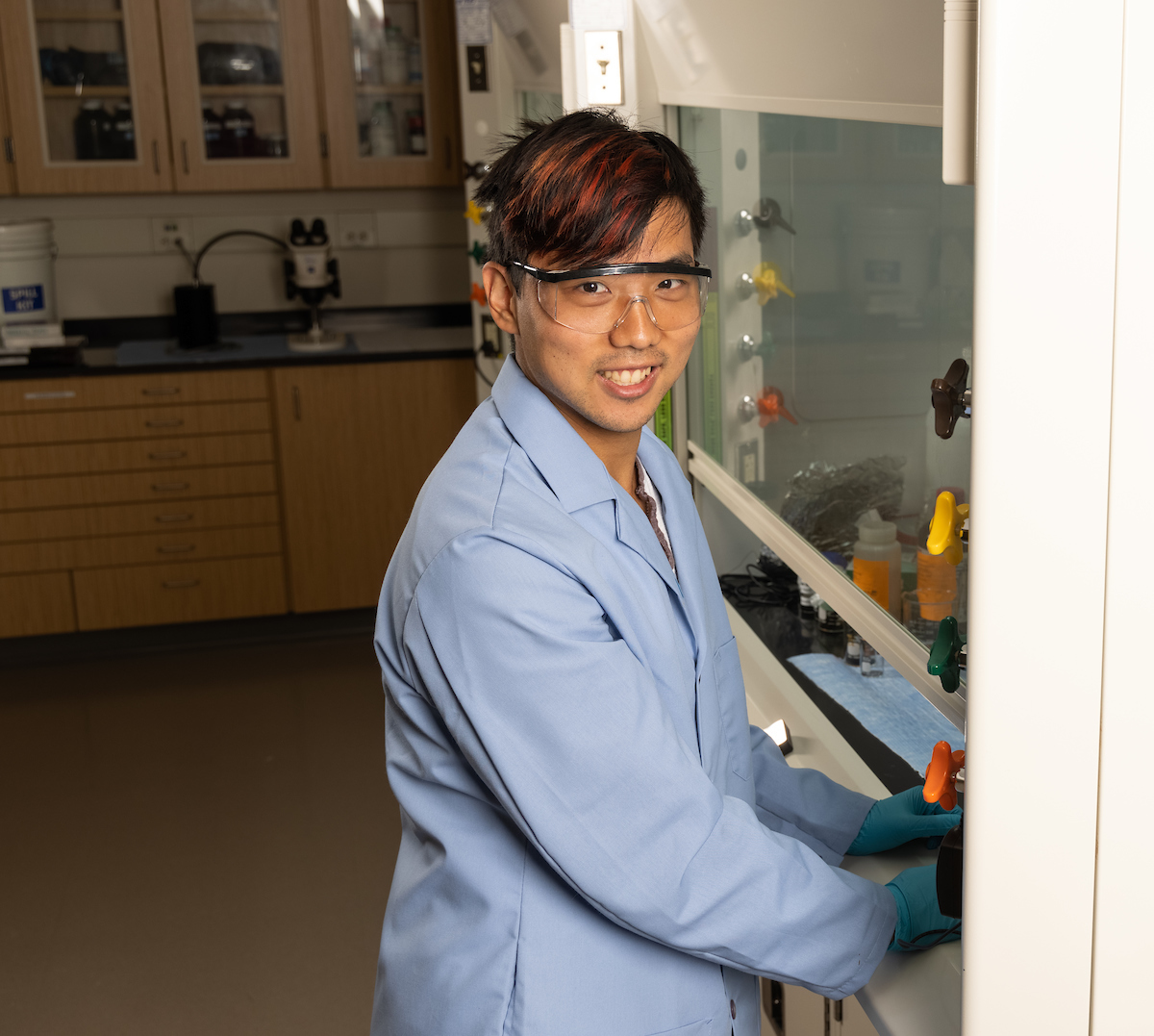

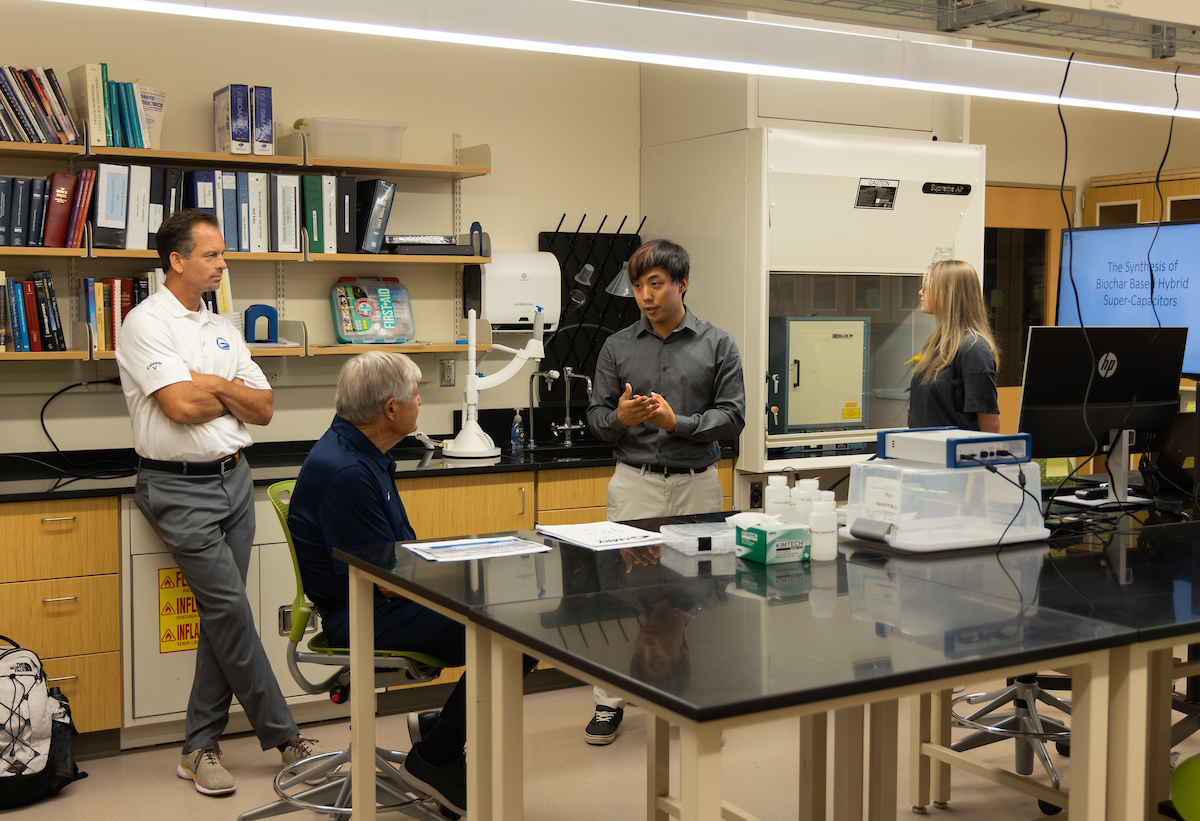

Team-based research is at the heart of the Werth Fellowship, which includes an eight-week summer program and an additional part-time component during the academic year. Undergraduate and graduate students work with faculty and local companies on scientifically related research initiatives. Recent projects have focused on sustainable nanotechnology as a rapidly growing interdisciplinary field that employs materials science and nanotechnology to address global sustainability challenges at the nanoscale. The fellows also participate in business-related workshops led by faculty from the School of Business, which touch on everything from intellectual property to marketing. Students receive stipends of up to $5,000 for their work.

The fellowship meshes perfectly with the Nanotechnology Center’s goal of enhancing Connecticut’s workforce competitiveness in nanotechnology and materials science, while also aligning with Southern’s focus on sustainability. The collaboration with the business community is a win-win for all involved. The student researchers have worked on high-level proprietary projects for companies. Werth Fellows, in turn, have the unique opportunity to learn from entrepreneurs and professionals about the business side of scientific research.

Werth and other executives from ChemWerth are among them. “Peter’s generosity extends well beyond the financial,” says Broadbridge. “As part of the program, he meets with the students and provides his comments and expertise as a mentor and role model. We have built this aspect into the program, and the student and faculty look forward to it every year.”

Werth also welcomes the opportunity to meet with the fellows. “I understand the level of research being conducted by faculty and students at Southern, and its importance to the community. I am not only a supporter but also a firm believer,” he says.

This summer, the Werth Nanotechnology Fellowship supported five undergraduates and one graduate student during the eight-week research program; their research continues during the semester on a part-time basis, also with stipends awarded. For the fellows, the combination of financial assistance and the opportunity to do hands-on research is potentially life-changing.

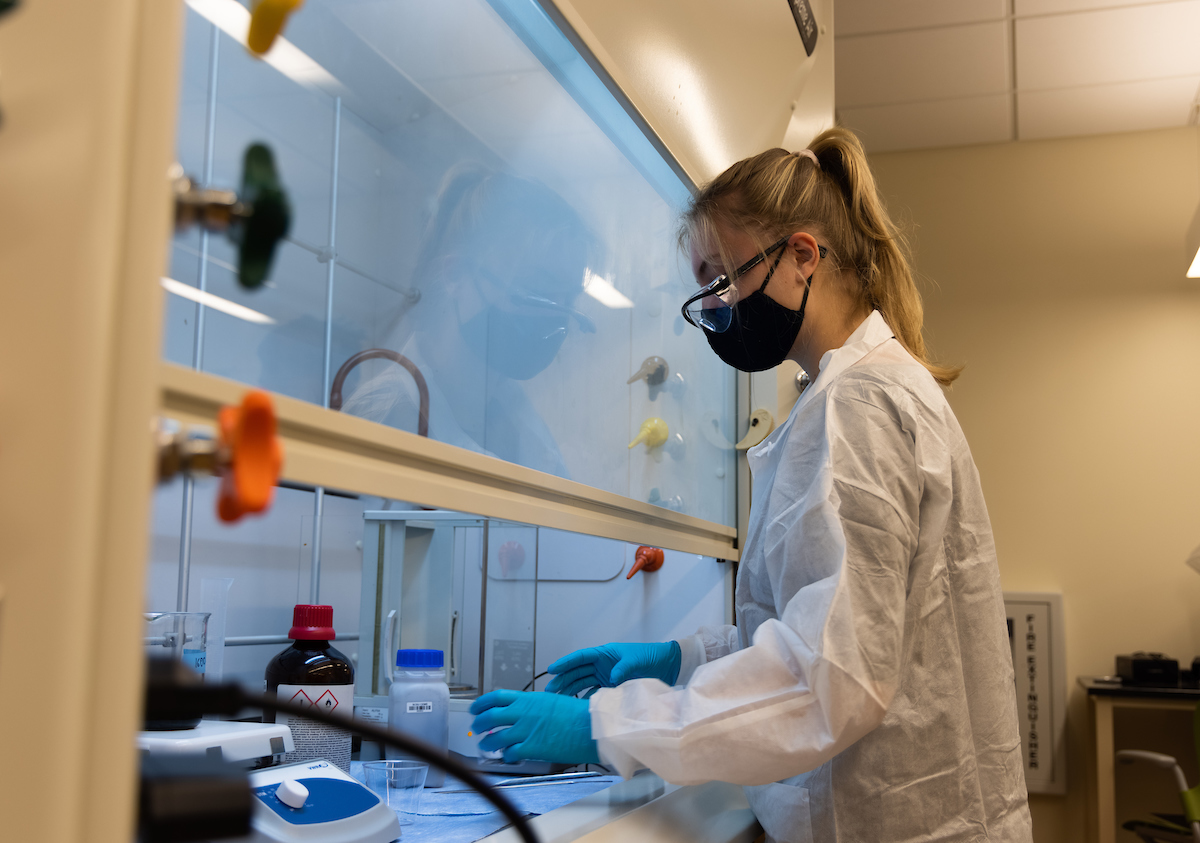

Emily Davis, a senior physics major with a concentration in secondary education, spent June and July researching fuel cells with a team that includes academic mentors as well as collaborators from a sustainable energy company. “We’re looking at the materials at an atomic level, trying to manipulate the atomic structure, and studying the way materials are composed. [When] we put hydrogen and oxygen into the cells, reactions take place within, and energy is produced. . . . Fuel cells are small, but stacks of them can be combined,” Davis says.

The summer has shaped Davis’ thinking, not only about her future, but also on big-picture topics. She was planning to pursue teaching, but is now considering whether she would rather be one of the researchers who are redefining energy practices around the world. She points to her teachers — both academic faculty and industry mentors — as influencing her reassessment.

“This has fully piqued my interest,” Davis says. “Research is not a linear process. There are obstacles, whether related to technology or sample preparation. The biggest thing our mentors taught us was to document everything, especially the failures. . . . Someone can take that information and use it in the next test. Some failures teach you more than successes.”

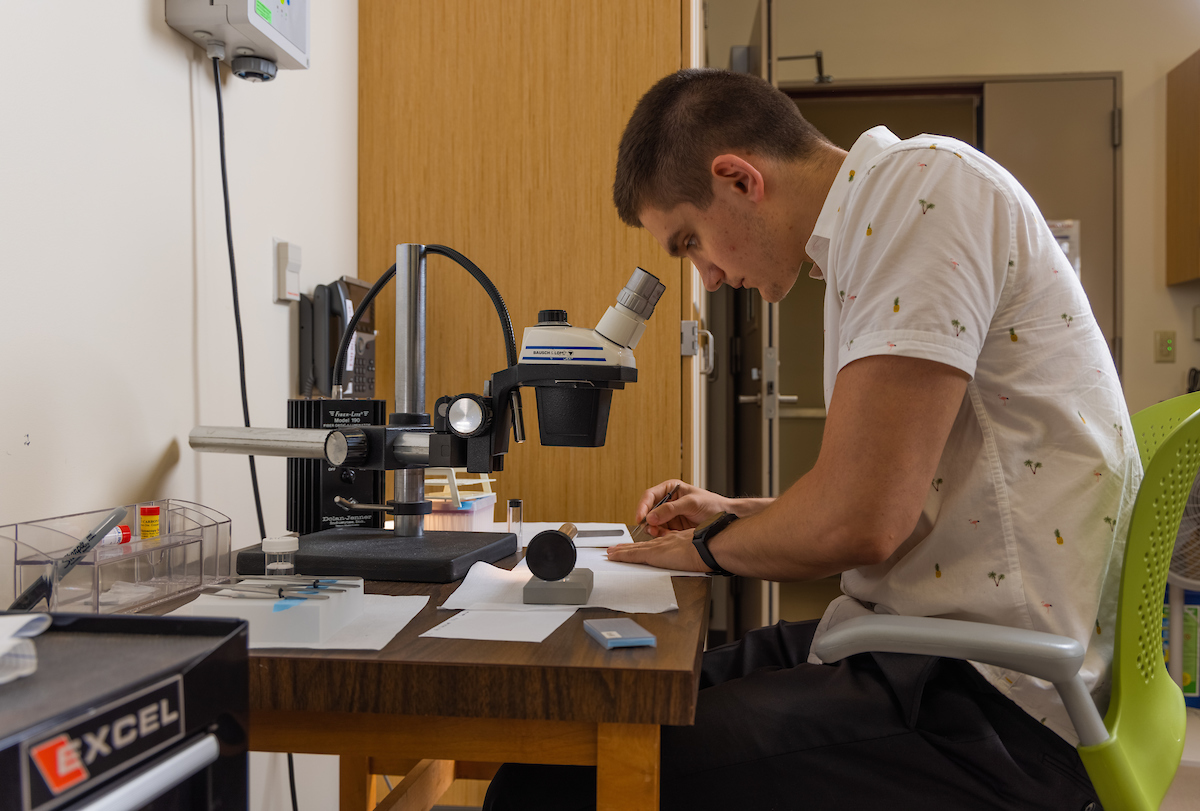

For senior Max Martone, on the other hand, the summer fellowship has reaffirmed his career plans. He will graduate next year with a degree in applied mathematics and physics, and intends to apply to a doctoral program.

“This was the first major research program I’ve been involved in, the most hands-on research I’ve done,” he says. “I wasn’t sure if I would like lab work. I was really apprehensive, but I really enjoyed it. I love it, actually. It was a great career eye-opener.”

Martone’s research was centered on super capacitors — energy-storage devices with up to 100 times the capacity of current battery technology. Specifically, his team researched biochar, a chemical substance similar to charcoal that is produced when plant materials are decomposed at high temperatures. It’s often used in agriculture to improve soil, but its high carbon content might lend itself to enhancing electrodes in super capacitors.

“Research by previous students gave us a foundation,” Martone says. “We are trying to learn what works better at maintaining charge/discharge stability. . . . There are so many aspects of biochar to be looked at. We used different parameters of the concentration of biochar, like a recipe, and we did find an optimal concentration.”

Both Martone and Davis have taken a winding road toward earning their degrees, transferring to Southern and changing majors along the way. The opportunity to participate in research as undergraduates clarified their goals, and the Werth Fellowship stipends helped ease the financial challenges of earning a college degree.

Davis, for example, notes that it will take five years to graduate. She had previously spent her summers hosting and waitressing, and worked as a tutor during the academic year. In contrast, the stipend awarded through the Werth Fellowship makes it possible for her to focus on her academic and career goals.

Werth understands the challenges facing Southern’s student body; about 53 percent of undergraduates who apply for financial aid are eligible for Pell Grants, awarded to those with the greatest level of need. He hopes his leadership-level support will inspire others to give. With that in mind, part of his most recent pledge will be used to create matching challenge grants during Southern’s annual Day of Caring.

“State funds are increasingly being used to keep Southern and other state universities operational,” says Werth. “To create a climate of excellence you need private individuals to invest in institutions like Southern and its students. I hope others follow to make similar investments in the future of Connecticut.”

*The Science of Effective Mentorship In STEMM, A Consensus Study of the National Academies of Sciences * Engineering * Medicine, 2019