A history power couple builds a life around examining the past — from Benedict Arnold to the American Civil War.

By Natalie Missakian

When Jeffrey Nichols, ’96, and Laura Macaluso, ’94, walk out the front door of the house they bought in Pennsylvania in late 2021, they see cornfields, cows, and a small lake — a view seemingly out of time. Their tiny village — Boiling Springs — has no traffic lights and looks much like it did in the late 19th century, when its founder, abolitionist Daniel Kaufman, helped smuggle enslaved people to freedom on the Underground Railroad.

The couple’s brick, Federal-style house, which was built in 1880, sits just down the street from where Kaufman lived. Hunkered down there on a snowy weekday afternoon last January, the couple spoke by phone about their long-term plans to restore their home, which sits on the Appalachian Trail and is a half-hour drive to Gettysburg.

“It needs work, but for a history major and an art history major, it kinda fits the bill,” says Nichols.

Macaluso chimes in, laughing, “Basically we were the only people who weren’t scared of it.”

It’s true, Macaluso and Nichols know a few things about historic houses. The couple, who married in 2001, spent years as caretakers of the 1700s-era Pardee-Morris House in New Haven, which was burned by the British during the Revolutionary War. They later oversaw colonial homes owned by the Milford Historical Society.

Then, in 2008, Nichols became executive director of what is arguably Connecticut’s most famous historic house — the Hartford-based former residence of novelist Mark Twain. Nichols later left the museum for a similar job running Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, the third president’s 317-acre private retreat outside Lynchburg, Va.

Meanwhile, Macaluso’s scholarly pursuits have gravitated toward the intersection of art, architecture, and history, including historical homes.

Her most recent paper, Benedict Arnold’s House: The Making and Unmaking of an American, was published in the October 2021 issue of the history journal Commonplace. Macaluso examines the life of the traitorous American Revolutionary War general through the lens of houses he bought or built.

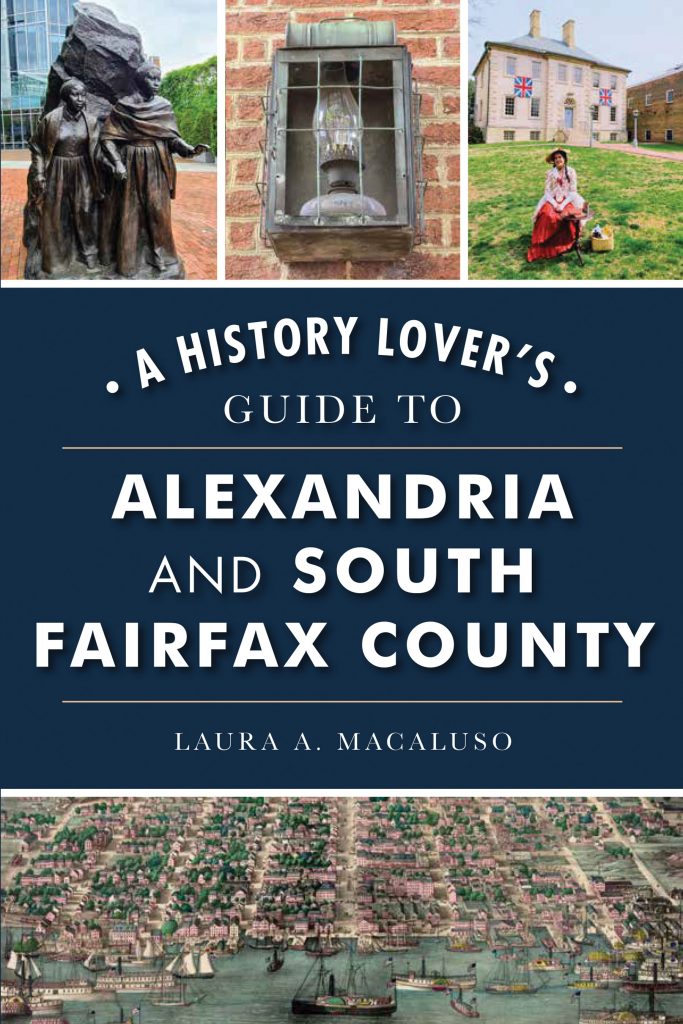

Now, with Boiling Springs as their home base, the couple is beginning a next chapter in their story as husband-and-wife historians. Nichols is less than a year into his new job as executive director of the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, Penn., while Macaluso is part of a team planning a spring excavation at the site of Benedict Arnold’s former New Haven home. In February, she joined the York County History Center in York, Pa., as the manager of institutional giving — and May 2022 will see the publication of her latest book: A History Lover’s Guide to Alexandria and South Fairfax County.

The couple’s own history dates to 1989 in Naugatuck, Conn., where they both grew up but never crossed paths. Nichols went to the local public high school; Macaluso attended Sacred Heart, a Catholic School in Waterbury. Mutual friends set them up on a blind date, and he took her to see Major League, which had just come out in theaters. They instantly clicked, but if their shared love of history cemented the bond, neither realized it at the time.

“I never really thought about whether that was a connecting point for us,” Macaluso says. “We were kids, and we were just having fun.”

Both ended up at Southern (Macaluso enrolled as a freshman in the Honors College and Nichols later transferred from Eastern) where they flourished in their respective majors. Nichols had planned to get his teaching certification but gravitated toward public history after volunteering in the curatorial department at the New Haven Historical Society (now the New Haven Museum) while at Southern.

Macaluso double majored in English and art history and minored in Italian at Southern, but it was art history that resonated most. She gives credit to dedicated faculty like David Levine and Camille Serchuk, professors of art history; a study abroad opportunity in Italy; and New Haven itself, with its rich historic architecture and free access to Yale museums.

She rekindled her connection to the Elm City years later. After earning her master’s in art history from Syracuse University in Florence, Italy, she took a part-time job with New Haven’s Arts, Culture, and Tourism Division. Then, while earning her doctorate in humanities at Salve Regina University in Newport, R.I., in 2016, she wrote her dissertation on New Haven’s public art collection.

It was through the city’s artwork that she became fascinated with Arnold, who was memorialized in the works not as a traitor, but as an early leader in the Revolution. A painting that hung in City Hall portrays his role in “Powder House Day,” when he demanded the keys to New Haven’s powder house to collect munitions before leading a local militia north to the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

“My particular interest in the Arnold story is to tease out the ways in which his image was crafted — both by himself and by others,” says Macaluso. “That’s why I take material and visual culture as historical evidence — and interrogate it and interpret it.”

Now, Macaluso is joining her friend Robert S. Greenberg, a New Haven historian, and state archeologist Sarah Sportman for an excavation at the site of Arnold’s former house on Water Street. Remnants of the home are buried beneath the parking lot of New Haven’s High School in the Community. The trio and other experts were on-site late last year, using ground-penetrating radar to scan for man-made structures to help inform the future dig.

Macaluso hopes the endeavor will ultimately shed more light on how Arnold lived and reveal the truth behind “myths and lore.” Among them, whether Arnold built a secret tunnel from his house to the harbor to smuggle goods.

“I’m interested in telling the full story, always and as much as possible,” says Macaluso.

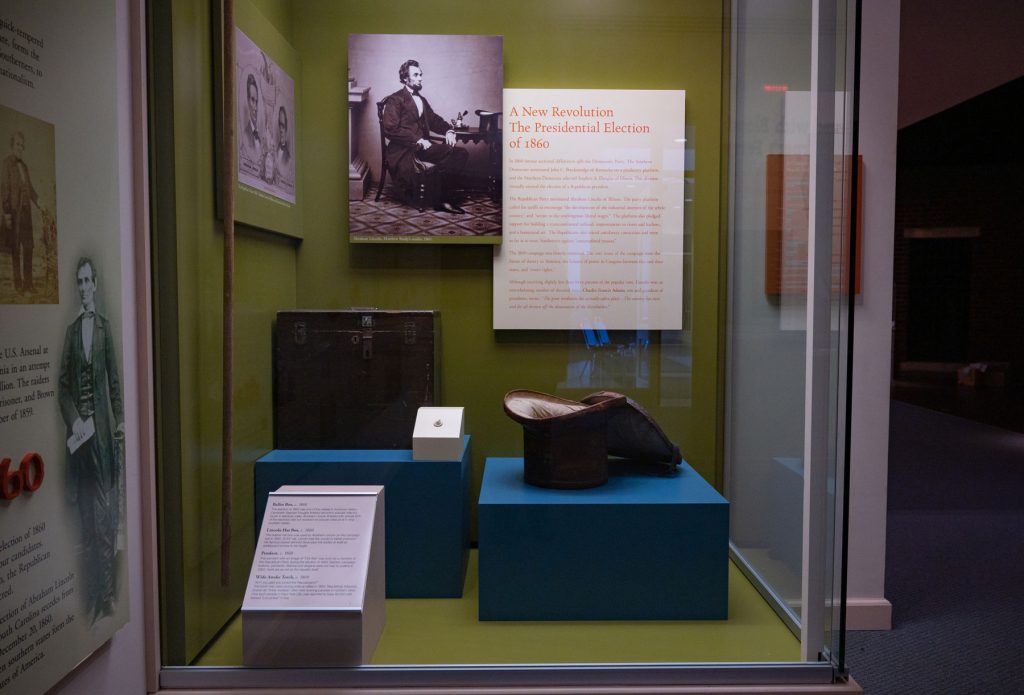

Nichols, who holds a master’s in museum studies from Bank Street College of Education and an MBA from the University of New Haven, is relying on the same approach in his new role at the National Civil War Museum, which boasts a collection of more than 25,000 artifacts, documents, and photographs and aims to present a balanced view of the war.

He recalls a story Jon Purmont, M.S. ‘64, Southern professor emeritus of history, told his students about English Civil War leader Oliver Cromwell, who, while sitting for a portrait, instructed the artist to paint him “warts and all.”

“I remember him saying that’s a good way to think about history,” Nichols says.

Nichols plans to introduce new educational programs at the museum that focus on the war and its legacy, including the unfulfilled promises of reconstruction. He also wants to tell the stories of marginalized groups, such as the 180,000 Black soldiers who fought in the war.

He credits Southern for teaching him how to think critically about history, a skill that’s especially crucial in today’s politically polarized climate, as debates rage over the removal of Confederate statues and as Congress continues to probe the events surrounding the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol.

“Obviously we live in an era that’s very challenging. We have a country where we are truly at each other’s throats,” says Nichols. “Looking back at Lincoln and the Civil War era is an important part of analyzing where we are today, and hopefully we can make better decisions than they did.” ■

Sharing History

Long connected to popular historical sites through his work, Jeffrey Nichols, ’96, continues to host history buffs and scholars as the newly named chief executive officer of the National Civil War Museum. The museum, which opened in 2001 in Harrisburg, Penn., has welcomed more than 950,000 guests from all 50 states and 39 countries. It features more than 4,400 artifacts and 21,000 archival pieces, including weapons, uniforms, and camp and personal effects, and is part of the Smithsonian Institution Affiliations Program.

Many Stories to Tell

Sharing history is a heartfelt pursuit for Laura Macaluso, ’94 — inspiring numerous projects. The author’s latest book A History Lover’s Guide to Alexandria and South Fairfax County (History Press), will be published in May 2022. Also slated for release this year: Objectify Benedict Arnold: Making Memory of America’s Traitor, a storytelling website created with Rachel Boyle of Omni History. Another digital exhibit — Celebrating CETA: When Public Art Made the Walls Talk — will expand on Macaluso’s 2019 showcase of the City of New Haven’s first community-based public art program. Lori Goldstein, manager of the Public Art Archive, is the co-curator.