In 2006, Camille Serchuk, professor of art history, was working on a project about French art in the 15th century when she discovered a previously-unknown map of France in a manuscript in the national library in Paris.

Uncovering and exploring that map launched her on a scholarly journey that has culminated in the exhibition entitled Quand les artistes dessinaient les cartes: vues et figures de l’espace français, Moyen Âge et Renaissance (When artists made maps: views and figures of France in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance). The exhibit runs through Jan. 7 at the Archives nationales in Paris.

Skeptical of the widely held belief at that time that the French hadn’t made any maps before the 17th century, Serchuk wrote to hundreds of French local archives to inquire what kinds of examples they had in their collections.

She received only a few replies. Most said either that they had no maps or only later printed ones; a few said, “this is a fascinating project but we really don’t know what we have,” and about a handful said, “Come! Look at what we have!”

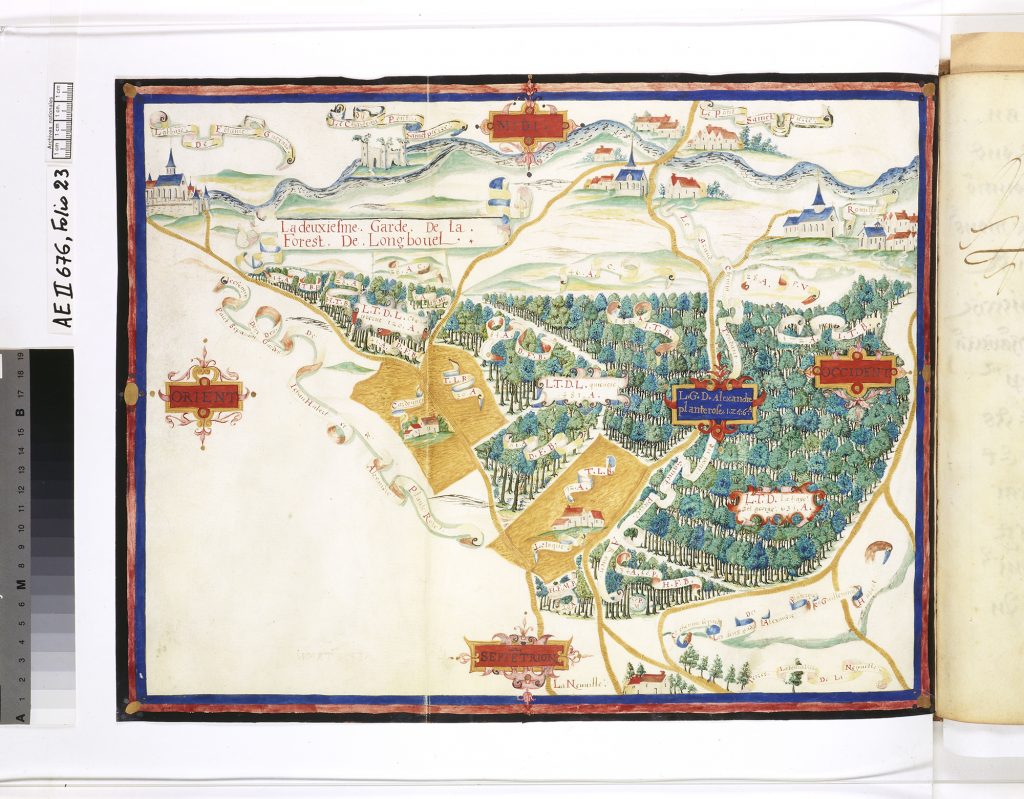

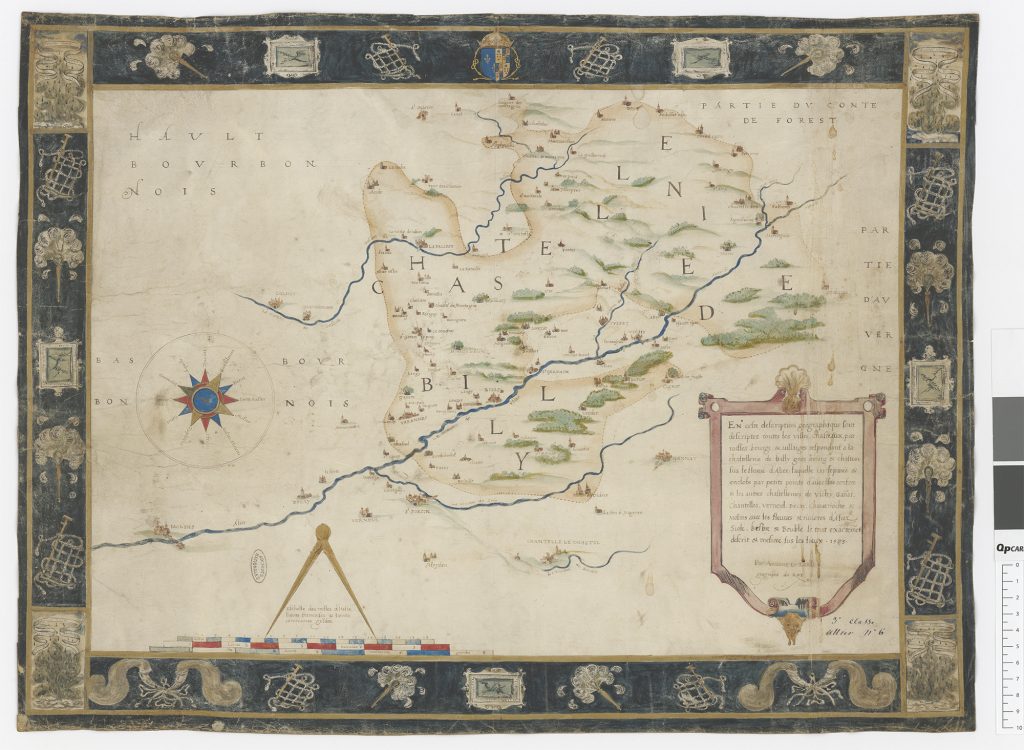

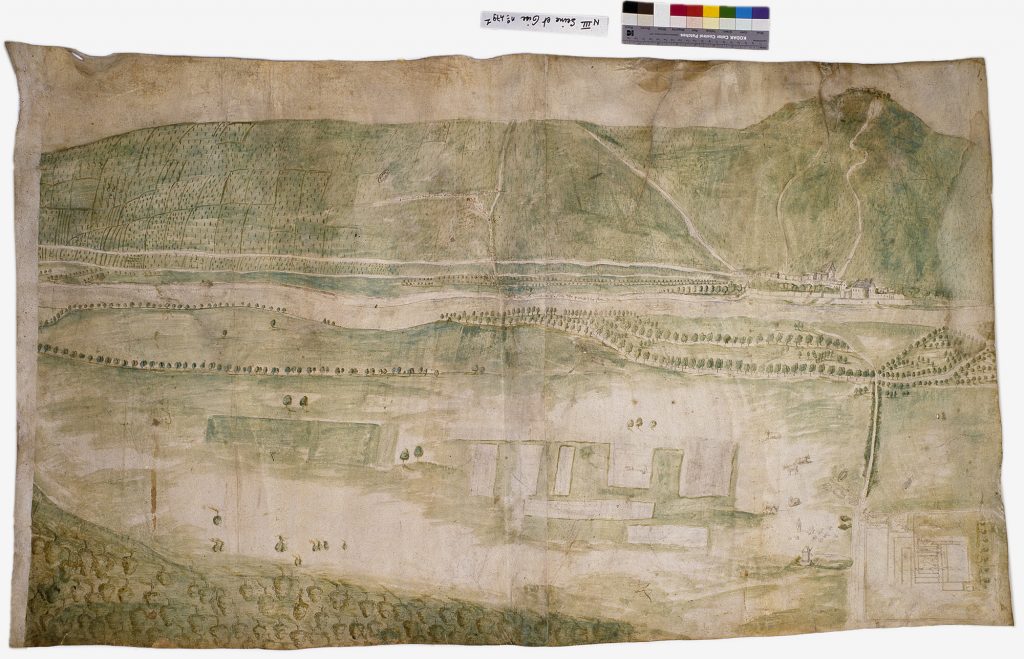

Following those leads she began to research about a dozen local and regional maps that were little-known or unpublished. Serchuk was fascinated to discover that many of the maps she was examining had been made by painters, and that they shared many features with artistic traditions of their time.

After delivering a paper at Oxford University in 2012 about one of these maps – depicting the forest of Thelle, in Normandy, drawn by two young artists – Serchuk met Juliette Dumasy-Rabineau, a medieval historian who had come to a similar conclusion: the French had a robust tradition of mapmaking in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance; it merely needed to be excavated from the archive.

When, in 2014, Dumasy had the idea for an exhibition of these maps, she contacted Serchuk to see if she would be interested in collaborating on it. Dumasy thought that an art historian, and an American, would bring a perspective to the project that would be different from her own and valuable to it.

Together, building on their prior research, they assembled a collection of items, organized them into themes and categories, and brought the project back to the national archives, where their team was joined by Nadine Gastaldi, the curator of maps and plans there.

The exhibition also explores the contribution of artistic traditions to cartography and how painters drew on the skills acquired during their training to make these maps, Serchuk said.

“Maps are not traditionally classified as works of art, but there is no doubt that there is considerable overlap in production methods and techniques, and the frequent role of painters as cartographers reveals how artists worked on a daily basis, between major commissions,” she said.

Indeed, many of these maps, or “figures,” as they were called at the time, were made by painters who were among the most renowned of their time (including Jean Cousin, Bernard Palissy, and Nicolas Dipre).

As such, they offer exceptional insight into the landscapes and scenery of everyday life at the turn of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance., Serchuk said.

Oddly enough, none of the maps in the exhibit were made to show the way from one place to another or to guide the traveler. Made at the request of prestigious sponsors (kings, princes, abbeys, cities), they were linked to practices of government.

The maps on display were produced by painters to delineate boundaries or legal rights, to resolve territorial disputes, to document public works, to support military operations, to describe historical events, to catalogue possessions, and to celebrate the identity of a place or territory.

At a time when cartography intersected with art, empirical observation took precedence over measurement in mapmaking, Serchuk said.

The painters drew on their expertise in drawing, composition, and perspective to create spectacular visual documents in a wide variety of media and formats, Serchuk said.

“Richly colored and abundantly detailed, these compelling images offer rich and unexpected insights into artistic and cartographic practice, and into the factors that shaped urban and rural landscapes during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance,” she said.

For more on the exhibit, visit: http://www.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/quand-les-artistes-dessinaient-les-cartes