Norbert K. Tavares, ’06, first attended college in Florida where he was discouraged from planning a career as a biologist, despite his passion for the field. “I wasted a lot of time pursuing majors that were hot at the time like computer science and pharmacy, but I didn’t enjoy them,” he says.

A move to Connecticut and subsequent transfer to Southern set Tavares on a better course. Today, he holds a doctorate in microbiology from the University of Georgia and is an American Academy for the Advancement of Science [AAAS] Science and Technology Fellow at the National Cancer Institute — where he helps lead the fight against the deadly group of diseases.

Last fall, he shared thoughts on Southern, finding a mentor, and the importance of diversity in science and other areas. Here are some excerpts.

What inspired your interest in biology?

I remember taking personality and career assessments early on in college that said I would be good at science and engineering, and not being surprised. I was mostly taking math and science courses, and enjoying them.

My specific interest in microbiology stems from reading about bacteria that could eat oil. Digging further, I learned about bacteria that could “breath” metals instead of oxygen, live in hot springs, and do all the other crazy things bacteria can do. I was hooked.

I grew up spending a lot of time outdoors – climbing trees, playing in the dirt and ocean. That coupled with a strong curiosity and wild imagination, there was only one thing I could be, a scientist or a transcendentalist poet, I guess.

Give us five adjectives that describe you.

Curious, contemplative, solution-centric, humanist, inclusive.

It seems that biology was an early calling.

I was wavering on sticking with biology because at the time you really needed a Ph.D. to go anywhere in the field, and I didn’t want to stay in school forever. I was also previously discouraged from pursuing a Ph.D. by a professor in Orlando, [Florida].

What changed?

When I transferred to SCSU I decided I would pursue biology because I enjoyed it. . . . Nicholas Edgington, [associate professor of biology,] was my assigned academic adviser. I told him about my goals, my interest in microbiology, my desire for a Ph.D., and to peruse an academic career. He listened and gave me specific, practical advice. He was the first academic adviser I had at three separate institutions who actually gave me good advice specific to my desires.

I did exactly what he said, starting with applying for and doing a summer research program for undergraduates at the University of Wisconsin. I then applied for and was awarded a Sigma Xi grant-in-aid of research after Dr. Edgington nominated me for membership to this scientific society.

I think he was surprised that I followed through with all of his suggestions. He then took me on as an undergraduate researcher in his lab. Because of the training I gained in his lab and the three other summer research programs, I was more than competitive for graduate school and was accepted into the number three microbiology program in the country at the University of Wisconsin. I owe a great deal to Dr. Edgington. He put me on the academic and professional path that I’m currently on.

What was your research focus?

My previous laboratory looked at how bacteria make vitamin B12. Bacteria are the only organisms that make the vitamin, which humans get from our diet via meat. There are no plant sources. The herbivores we eat, like cows, get B12 from the bacteria in their guts. I studied the genes and enzymes that bacteria use to make B12.

What is your current position?

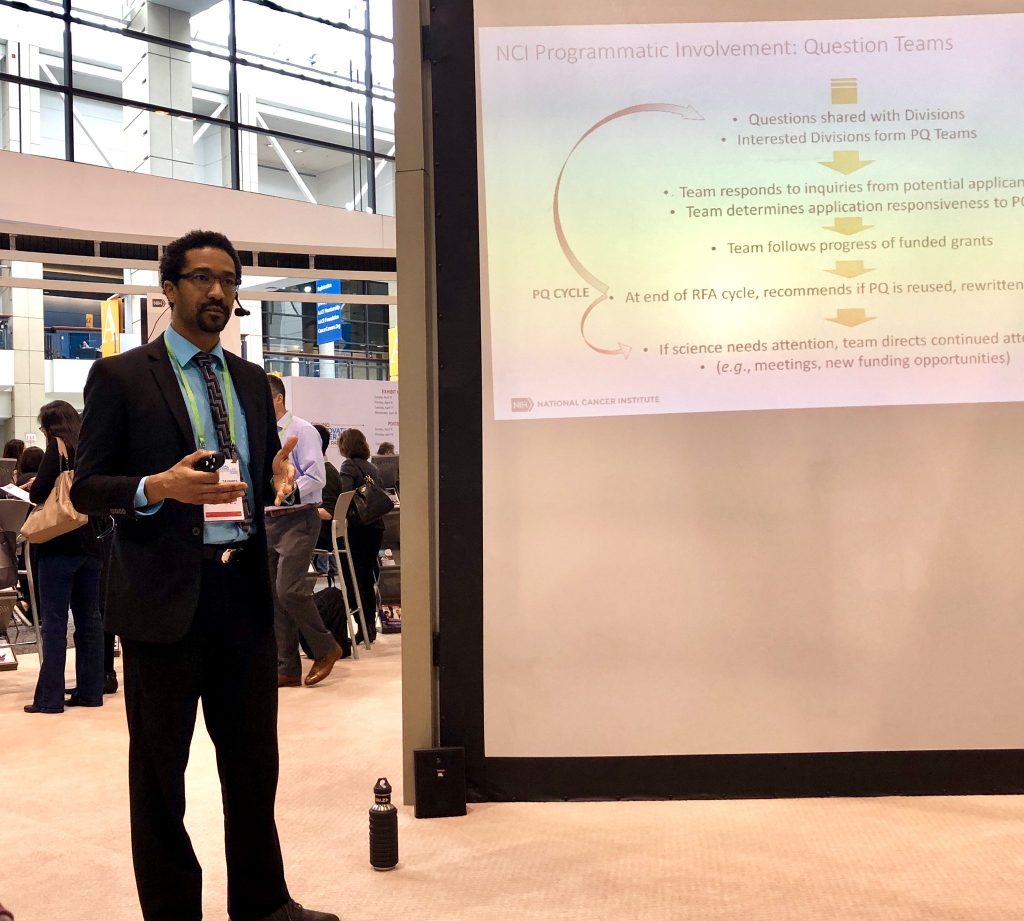

I am an AAAS Science & Technology Policy Fellow at the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health in D.C. I work in a center that analyzes the cancer research landscape – and builds programs and collaborations to develop technology, standards, and innovative ideas to fill the gaps in cancer research and move the field forward. In my role, I analyze the cancer research field to find these gaps and opportunities — and manage and evaluate the existing programs we have built. In other words, I build and fund grants, infrastructure, and programs to help cancer researchers study, understand, treat, prevent, and eventually eliminate cancers.

Your bio with the National Cancer Institute lists your strong interest in the advancement of women and underrepresented individuals in science and other areas. Can you talk a bit about that commitment?

If you have at least two women in the room — whether that room is a meeting, a board room, or Congress — it changes the conversation in a way that is important. You’ve heard it said, “If there’d been a woman in the room at the time this idea was put forward, it never would have happened. We would not have made this mistake.” I believe that’s true. Whenever I write a policy document, I always make sure to get it in front of the eyes of a number of different women. And the things that have come back – “Hey, maybe you should change this.” – I would never have thought of without their input.

I’ve learned you need to have that diversity, and there’s data to back it up. If you have lots of diversity, you tend to have a slower start. But the group makes much greater progress and they are more creative.

We live in America during sensitive times and race has always been and will continue to be a touchy topic. I am a scientist – and, as I mentioned earlier, there is good data that shows diversity matters. If a girl has had a woman math teacher, she’s much more likely to excel in the subject and choose it as a major. I’m much more likely to pursue the sciences as a career if I’ve had a science teacher who is African American. It makes a difference . . . and I think the influence occurs as early as elementary school.

The truth is this is passive. . . . But I really believe existing in the world as an African American Ph.D. – as a scientist – and trying to do well is important and hopeful. Increasing exposure [to my educational and career path] is part of my obligation. And if I can maybe inspire another African American to study the sciences – or maybe go to Southern or another college – I am happy to do it.